Kawabata searches for deeper truth, turning the tea ceremony into a chamber of guilt, desire, and inherited shame.

Yasunari Kawabata’s Thousand Cranes turns the Japanese tea ceremony on its head. What is usually a spectacle of beauty and restraint—a refuge of calm, clarity, and refinement—becomes instead a chamber of guilt, desire, and contamination.

When I first encountered the tea ceremony as an art student in London, whisking bitter matcha in my dorm room and confusing everyone in the hallway, I understood it only as an aesthetic practice. Later, reading Okakura Kakuzō’s The Book of Tea, I learned its greater significance: tea as an antidote to chaos, an invitation back to stillness and purity. Kawabata’s novella offers the opposite. Perhaps the truer, darker underside of an “elegant” gathering anywhere. It shows what happens when impurity enters a space built to contain beauty.

The story follows Kikuji Mitani, son of a respected tea master whose legacy is tainted by a string of affairs. The world Kikuji inherits is one of lingering shame, and every tea gathering he attends seems to stir old ghosts from his father’s past. Chikako Kurimoto, his father’s former mistress—now a meddling, intrusive presence—tries to arrange a marriage between Kikuji and the graceful Yukiko Inamura, whose pink kerchief embroidered with cranes gives the novel its title.

But Kikuji feels the gravitational pull of another figure: Mrs. Ota, also a former lover of his father, a woman burdened by decades of guilt so heavy it becomes fatal. Despite their age differences, their affair is immediate and sorrowful, driven by longing, shame, and that odd mix of pity and desire Kawabata renders with understated precision.

The plot is spare yet emotionally charged. Desire tangles with remorse; attraction carries the residue of inherited sin. The tea ceremony—normally a choreography of calm—becomes a stage for unease. Every bowl, cloth, and utensil feels touched by someone’s pain. Beauty, in Kawabata’s hands, is never neutral, never safe.

“Kikuji remembered the tea bowl Chikako had placed before the girl. … It had passed from Ota to his wife, … and from Kikuji’s father to Chikako; … there was something almost weird about the bowl’s career.”

What stood out to me most is Chikako. In a tradition that values female grace and unobtrusiveness, she is abrasive, manipulative, impossible to ignore. Kawabata describes her large hairy birthmark in an unforgiving detail. Today, it may read as body-shaming, but in the symbolic economy of the novel the blemish is not just physical: it represents moral stain, the intrusion of defilement into a space meant for purity. Kawabata, like Mishima or Murakami, anchors meaning in the body; this time using a physical flaw to embody corruption, resentment, and unresolved desire.

“The locus of this disgust is the disfiguring birthmark on her breast. ‘Chikako was unmarried because of the birthmark,’ his mother observes, bluntly.”

Written as a newspaper serial from 1949 to 1951, Thousand Cranes has a tight, coiled intensity unlike the drifting lyricism of Snow Country. Critics such as Donald Keene have called it the other novel’s “darker twin”: where Snow Country is fleeting, expansive and melancholic, Thousand Cranes is intimate, claustrophobic, and morally charged. Its symbolism is sharper. Its emotional palette poisonous and acidic.

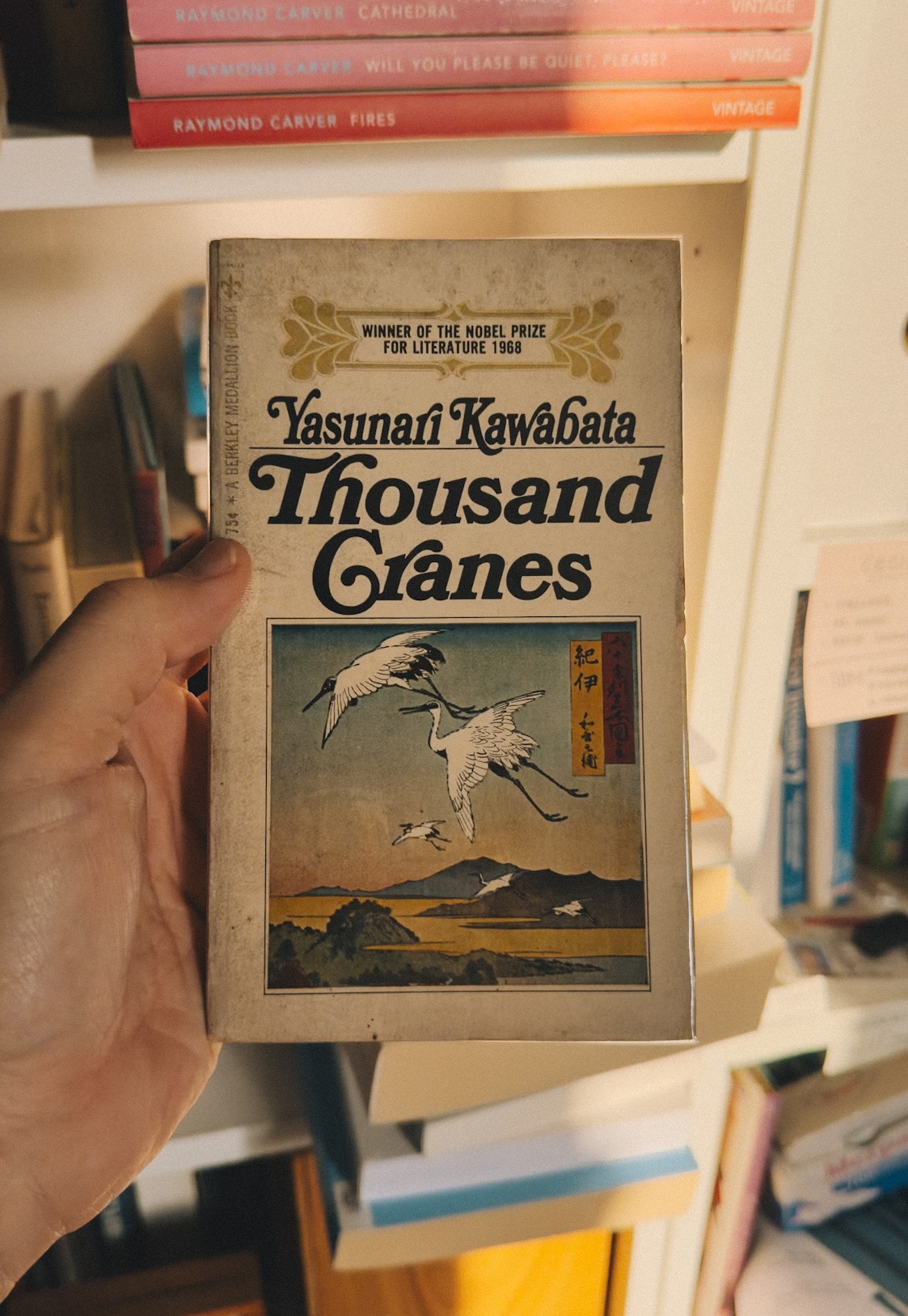

The Nobel Committee singled it out in 1968, praising its “masterly” use of symbolism. It distills traditional Japanese aesthetics such as wabi-sabi, mono no aware into a modernist tragedy that the West could appreciate.

And for all its beauty, Thousand Cranes is deliberately unsettling. It suggests that harmony is fragile, easily polluted by desire, memory, and the echo of old sins. The tea ceremony here is not a sanctuary but a reminder that grace can be undone by a drop of disruptive presence.

For readers curious about Japanese aesthetics and the cultural philosophy behind the tea ceremony, this novella is essential. But for pure emotional resonance, Snow Country remains, for me, the more significant and haunting work. As someone who has practiced chado, I return often to Sen no Rikyū’s teaching: “If you do not have tasteful utensils, it is better not to hold a tea gathering.”

Kawabata’s Thousand Cranes is a testament to how easily that beauty and purity is lost. Not only through objects, but through the human heart itself.