Why Seneca’s Stoicism Matters More in an Age of Crisis Normalization

For many readers today, Stoicism has become shorthand for an emotional-discipline hack that promises focus, less anxiety, no drama, better productivity. From The Daily Stoic to the closer-to-home Filosofi Teras, the philosophy has been repackaged as an everyday toolkit: a clean, actionable method for staying calm amid everyday conflicts, deadlines, and the noise of social media. It works. It has introduced millions to an ancient school once seen as marble-hard and forbidding, at a moment when an overworked, anxious generation living through a normalized state of crisis needs a guiding light. But for readers who want to go deeper, Stoicism is more complex, darker, more elastic—and no writer reveals that complexity more vividly than Seneca.

Most contemporary readers enter Stoicism through Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations, a book so composed in temperament it often feels as if it were written by a god lounging on Olympus. Marcus speaks like a man counseling his conscience in the dark—serene, dutiful, impossibly noble. His Stoicism is aspirational. He treats virtue as something that, with enough discipline, allows a person to rise beyond ordinary human limitations. Even when he scolds himself, the tone is priestly, like the words of a deity from above.

Seneca could not be more different. If Marcus writes from a sunlit summit, Seneca writes from the dark undertow. To read Letters from a Stoic is to feel grounded in the cold facts of life—earthly, melancholic, unsparing. His sentences twitch with uneasy self-awareness. He advises himself because he does not fully trust himself. He urges calm because he is afraid. He praises poverty while surrounded by wealth, preaches virtue while navigating a court soaked in treachery, and speaks of spiritual freedom while living under the eye of the tyrannical, self-indulgent Nero. His tone is not serene but strained—elegant, yes, but edged with defensiveness and self-reproach. You sense a man trying to stay upright while the floor trembles beneath him.

Context sharpens this impression. Seneca spent years in forced exile. His body tormented him. Asthma, chronic illness, bouts of despair so violent he contemplated suicide—he tells us he once stayed alive only because he feared his father could not bear the loss. When he returned to Rome, it was to serve as tutor and adviser to the young Nero, a role that would eventually doom him. He accumulated wealth, influence, and enemies in equal measure. And when Nero turned paranoid, Seneca was ordered to take his own life. The chilling shadow of that ending falls backward across his letters, darkening even his most confident assertions.

This is why his prose feels modern. Seneca does not write as a sage handing down eternal truths. He writes as a man hanging on in a storm, trying to pass along whatever fragments of stability he can to a younger friend—Lucilius, a procurator of Sicily. Unlike Marcus, who writes privately to himself, Seneca writes to someone who still must move through a dangerous world. The letters are part mentorship, part self-examination, part last testament. Philosophy forged under duress.

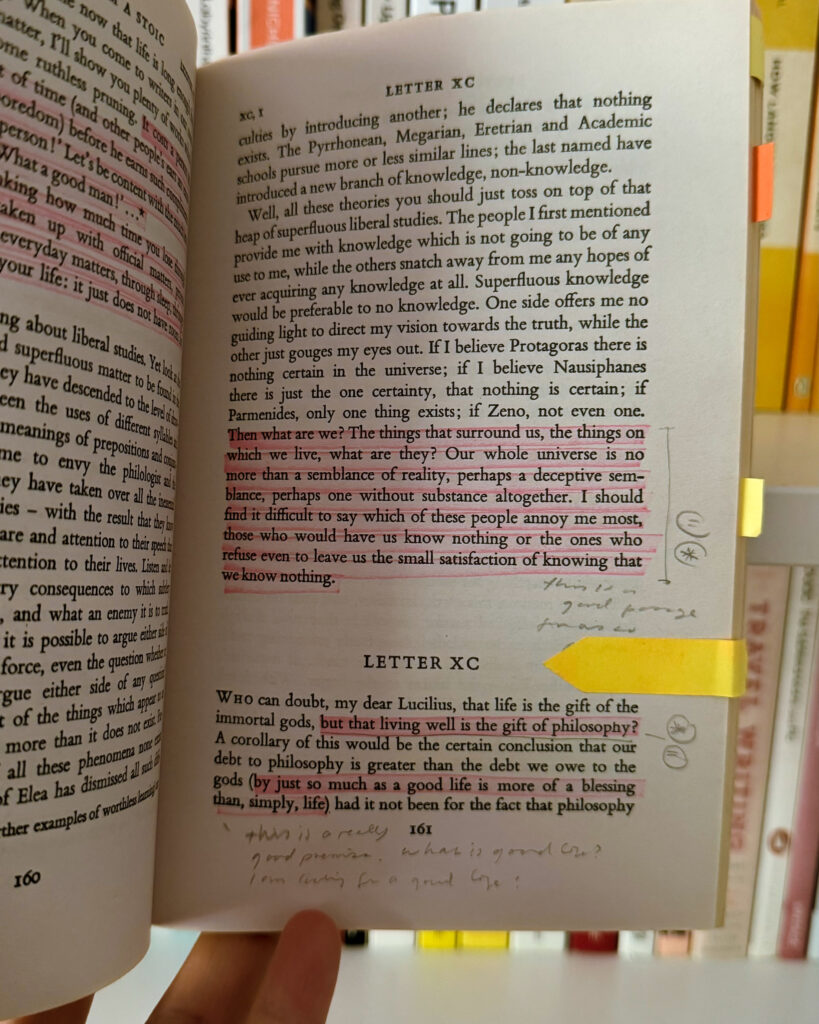

Who can doubt, my dear Lucilius, that life is the gift of the immortal gods, but that living well is the gift of philosophy?

Placed beside Marcus, the contrast becomes illuminating rather than diminishing. Marcus tries to rise above the storm. Seneca tries to endure it. Marcus’s Stoicism reaches upward, toward self-perfection. Seneca’s reaches inward, toward self-preservation. Both share the same moral skeleton—virtue over impulse, reason over fear—but their emotional textures are worlds apart. These are the many faces of Stoicism. Unlike the single-minded utility tool of modern handbooks, classical Stoicism also wrestles with metaphysics, theology, cosmology… Even the nature of reality itself. As Seneca writes, in a passage that uncannily anticipates Kant centuries later:

Then what are we? The things that surround us, the things on which we live—what are they? Our whole universe is no more than a semblance of reality, perhaps a deceptive semblance, perhaps one without substance altogether.

Seneca’s contradictions—often used against him—are precisely what make him compelling. His letters are shot through with awareness of his own failures. He knows he is compromised. He knows he does not always live the ideals he praises. But instead of concealing these tensions, he writes through them. The result is a Stoicism far more genuine than the polished quotes circulating online: not a path to greatness, but a method for not falling apart.

That tension between the philosophy he teaches and the life he lives gives the letters their extraordinary charge. When Seneca urges Lucilius to withdraw into himself, he is not offering an abstract principle; he is offering a shelter he built in desperation. When he warns against anger, it is because he feels its tremors inside him. When he speaks of the shortness of life, you sense a man who fears that his end is near.

…refuse to let the thought of death bother you: nothing is grim when we have escaped that fear.

In this way, Letters from a Stoic captures an often-missing face of Stoicism: a philosophy for those who come to it injured. Many modern readers discover Stoicism not through ambition but through hardship—illness, grief, burnout, the slow erosion of daily pressures. Seneca speaks directly to that audience. He understands that philosophy is sometimes less a path to enlightenment than a handhold carved into a cliff. Seneca does not promise calm. He offers clarity in crisis. He does not preach transcendence. He shows how to survive.

If the modern Stoic movement is the shaped metal—the ready-made tool for specific purposes—Seneca takes us back to the molten core. His letters remind us that philosophy is not a product but a material: heated, hammered, bent, re-formed under pressure. And for readers willing to look past the smooth surface of contemporary Stoicism, Letters from a Stoic reveals something different: not perfection, but humanity under strain. Not serenity, but endurance. Not a map, but a grip.